Massive Google fail. Since days of searching have brought me no closer to answering my most pressing Chinese font questions, I bit the bullet and sat down to do some testing and write up my own guide in English for Western web and UI designers targeting users in China (yeah, all three of us).

Everything I’ve written here is the fruit of my own experiments and tests, so if you notice something I’ve missed, do write me a note at me@kendraschaefer.com

First things first: What are the standard simplified Chinese web fonts?

| Windows | OS X |

|---|---|

| ???SimHei | ????: Hiragino Sans GB [NEW FOR SNOW LEOPARD] |

| ???SimSun | ?????STHeiti Light [STXihei] |

| ????NSimSun | ?????STHeiti |

| ???FangSong | ?????STKaiti |

| ???KaiTi | ?????STSong |

| ??_GB2312?FangSong_GB2312 | ?????STFangsong |

| ??_GB2312?KaiTi_GB2312 | |

| ??????Microsoft YaHei [as of Win7] |

Good Rules for Using Chinese fonts in CSS

Use the Chinese characters, and also spell out the font name

When declaring a Chinese font family, it’s typically a good idea to type out the romanization of the font (for example, “SimHei”) and declare the Chinese characters as a separate font in the same declaration. What this does is help reference the font file regardless of weather it’s been stored in the local system under its Chinese or western name – you’re covering all your bases here.

Example:

font-family: Tahoma, Helvetica, Arial, "Microsoft Yahei","????", STXihei, "????", sans-serif;

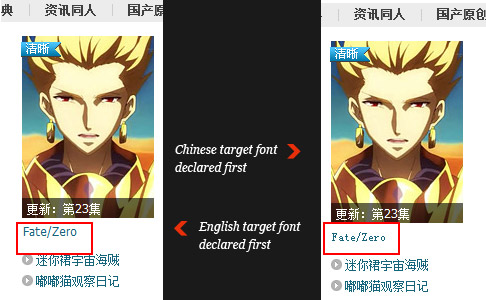

Declare English target fonts before Chinese target fonts

I’m sure someone’s come up with a standardized rule on this, but I’ve never seen one, so here’s mine: always declare all your target English fonts first. Why? Because English language fonts do not contain the glyphs for Chinese characters, but Chinese fonts do contain a-z characters. What that means is that if you declare your Chinese fonts before your English fonts, any English-language computer that has the standard Chinese font faces installed will display English characters using Chinese fonts, and let’s be honest, English letters in Chinese font families are fugly.

On the other hand, if you declare your English fonts first, Roman characters will be rendered in the first font, and Chinese characters will be displayed using the fall-back (Chinese) font. This should apply even if your site is mostly in Chinese or is targeting a wholly Chinese audience, because English characters will pop up in Chinese language sites as a matter of course – in usernames, for example.

Code example:

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", "Microsoft YaHei", "????", STXihei, "????", serif;

Declare the Microsoft font and the Mac font

Just like with English-language fonts, you should declare at least one Chinese font for Windows and one Chinese font for Mac (as with the Arial / Helvetica nonsense). Which one you declare first should depend first on the platform you’re targeting.

Do I have to put quotes around Chinese fonts in font declarations?

No. I asked for input on this and a few readers have responded. You do not need to do this:

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", "Microsoft YaHei", "????", STXihei, "????", serif;

You can do this:

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", "Microsoft YaHei", ????, STXihei, ????, serif;

A look at the major Chinese fonts

??12? – SimSun 12pt font

??, or SimSun, is by far the most commonly used base body font in Chinese web design. Personally, I dislike SimSun, in the same way many designers dislike Arial. It’s a bit heavy on the aggressively utilitarian boringness. But if what you’re looking for is the de-facto, big-uncool-websites-all-use-it Chinese font, you’ve found it. It looks like this:

Example site: Chinese video sharing site http://www.tudou.com uses SimSun as base body font.

Declare that shit:

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, tahoma, verdana, ??, SimSun, ????, STXihei, sans-serif;

???? – Microsoft YaHei

Microsoft YaHei is in my opinion, the Helvetica of the Chinese font world – it looks nice in most sizes (the Mac font equivalent is probably STXihei, the “light” version of STHeiTi). I find it’s modern, fresh and clean, and like a Rubenesque lady, is thick in all the right bits. It looks like this:

Example site: This very nice Baidu blog users MS Yahei as base body font. Astute Chinese reader and web developer DaiJie (check out his Chinese language blog, if you’re so inclined) points out that SimSun is the fall-back font for Microsoft YaHei, which was introduced as of Windows 7, and Yahei doesn’t display on older machines. He says:

“Yahei is installed on Windows7, but still 68% of Chinese (os.data.cnzz.com) users using WinXP. We fallback to SimHei usually, but it is not as good as Microsoft YaHei. SimHei and Yahei both look good at a large font size, but are not clear enough when the font size is below 16px. When font size is large than 16 px, SimSun looks ugly. So, [we commonly use] YaHei for the title font and SimSun for the body font.”

Declare that shit (updated to add Simsun fallback):

font-family: Tahoma, Arial, Helvetica, "Microsoft YaHei New", "Microsoft Yahei", "????", ??, SimSun, STXihei, "????", sans-serif;

?? – FangSong

FangSong is a relaxed, vaguely scripty font – maybe you could equate it to a Chinese serif. I feel that, like with many script fonts, it really does need a 14px base font size or above. It looks like this:

Declare that shit:

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", "FangSong", "??", STFangSong, "????", serif;

?? – KaiTi

Kaiti is another script font that’s a little roomier than FangSong with slightly more shapely strokes (very slightly), and the character spacing is just a little bit wider. I find that Kaiti doesn’t do well below 14pt. It looks like this:

Declare that shit:

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", "KaiTi", "??", STKaiti, "????", serif;

What’s the deal with Chinese characters and @font-face?

Considering that most Chinese font files are kinda ginormous and typically include at least 3000 base glyphs, Chinese doesn’t lend itself very well to @font-face embedding. Many of my non-standard Chinese fonts run upwards of 5MB, and the @font-face generator over at Font Squirrel has a 2MB file size limit. So, while it’s impractical on a CMS platform where you’re dealing with a bunch of user-generated data, that’s not to say it can’t be done.

You can use the CodeAndMore fontface generator to skip over Font Squrrel’s file size limit if you’re so inclined.

Typekit-style systems for Chinese fonts

[November 15, 2013 UPDATE:] There is another way. I just found out about a company called JustFont based out of Taiwan that offers a Typekit-style font hosting for Chinese @font-face style fonts. They’ve got a decent library of font options, both for simplified and traditional Chinese characters (less for Simplified characters, but that may change in time). Problem: they don’t have an English-language interface, so if you can’t work in Chinese, you’ll have a problem using the site. They do, however, offer Facebook sign-up, so you’ll be able to get that far at least. [Sept 5, 2014 UPDATE:] Aaaand another one: Youziku.com. This one is awesome – they have a much bigger font library than JustFont. My shop has tested these guys out, and for the most part, everything works well. They offer three embedding methods for their fonts, but only the webservice script really gives you similar usage freedom to @font-faceTwo issues that I’ve found: extra-thin fonts displayed at small sizes come out looking super ragged to the point of being unusable. And two, if you use their hosted service, there’s a little jump on page load – the page loads the content first then applies the font to it, so you see unstyled characters for a split second before the font settles into place.What’s up with the new free font, Source Han Sans?

So, Adobe, who put out Source Sans (English) font a few years ago, teamed up with Google in summer 2014 to release Source Han Sans, the best thing to happen to Chinese web fonts basically ever. Though these fonts are not yet available as hosted fonts on English servers (desktop version only on Typekit and Google as of Dec 2014), the font is hosted on Youziku.com, under its Chinese font name, ????. Best thing about this is that unlike most Chinese fonts, this one comes in 7 weights all the way from Extralight to Heavy – yeah, baby. I hope to see this on Google / Typekit as a hosted option soon.

And what about Noto Sans Hans?

Google is currently (Dec. 2014) working on a free font called “Noto Sans” (here’s the project page), which aims to support all the world’s languages. There are Chinese versions available for download, but these are not hosted on Google webfonts yet. The font’s lovely, though – you should get it. Google does offer an “Early Access Webfonts” page, where you can snag embedding code for experimental fonts. There are a couple of Traditional Chinese fonts there, but no Simplified fonts yet. A few versions of Noto Sans also support Pinyin.

What’s the deal with Google Fonts and China?

Mainland Chinese internet users are no longer able to connect to the Google Font API since the government blocked access to Google. Having a Google webfont on your Chinese website basically hangs the loading process for ages for users based in China as the site tries to render the font. Sometimes it works, mostly it fails. No one ever said life was fair.

[December 12, 2014 UPDATE:] So, Qihoo 360 is hosting a Google webfont mirror for Chinese users. If your site is only targeting China, you can use the Qihoo 360 mirror to load Google webfonts. If your site is targeting both China-based and non-China-based users, the recommendation is to load a script that decides which webfont source to use based on the user’s IP. Get the details on SEO Shifu.Need a custom Chinese font or logotype made?

Makefont.com: These guys are hot-shit design-y Chinese typographers. And buy their ready-made fonts, they’re really cool.

What’s the difference between Big5 and GB2312 Chinese fonts?

Quick history lesson: About 50 years ago, Chairman Mao controlled mainland China. And he decided that literacy rates were super low because Chinese characters were crazy complicated to write. So he decided to “Simplify” the whole written language. He hired some linguists, they came up with a writing system that removed a ton of the strokes from many of the characters, reducing the complexity of written Chinese.

Problem: Mao’s little plan only effected the people in Mainland China. That means that all the Chinese people living outside of Mao’s sphere of influence – people in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Chinese immigrants to the U.S. and abroad – didn’t adopt the new system at all. So now, Chinese characters can be written two ways. One way is the old way, “traditional characters”. Or, as we call it in fonts on the web, Big5. The other way is the new way, used only in China proper, “simplified characters”, or GB2312.

If you are choosing fonts for a site that targets mainland China, choose GB2312. If you are targeting Hong Kong, China towns abroad and immigrant communities, Taiwan, etc., use Big5. Most Chinese websites offer both on multi-lingual platforms. The fonts on this page are all GB2312, but most have Big5 versions.

(Dear type-A devs: yup, I know. I know what an encoding is. It’s just easier to explain this way, kthxbye.)

How to find more Chinese fonts on the web

The English web-o-verse is sadly lacking in Chinese font options, and because creating a Chinese font face is such a ridiculously huge undertaking, there are far less Chinese fonts than English ones. However, there are still quite a few. Best thing to do is pop over to Google or the Chinese search engine Baidu and have a search for:

???? – Chinese Fonts

?????? – Free Chinese Fonts

Look for the characters ?? – this means “download”.